Let’s face it, dialogue can be a pain. Too often characters are let down by poorly constructed dialogue that makes them sound forced. But in visual mediums, comics especially, even great dialogue can be let down by the presentation of the scene.

The last thing you want is a repeat of the same two panels as characters talk back and forth. No matter how good the dialogue is, the stagnant art direction will have readers skipping to the next page. And anything that causes readers to skip is a cardinal sin in writing.

Even if your story is all about the action, those impressive visuals won’t hold up unless we are emotionally involved with the characters and their goals. Basically, at some point, you will have to script a conversation. In this article I’m going to show you the three examples that taught me the most about presenting lengthier conversations that not only keep your readers hooked on the dialogue, but enhance it as well.

Let’s look at my favourite example from Alan Moore’s Watchmen.

Where to begin!? First of all let’s get to grips with what is happening on the surface here, the page depicts two scenes running parallel to each other: an interview with Dr Osterman and a fight scene involving two of his fellow retired “superheroes” against a gang that made the wrong choice by thinking they could be victimised. This is a page steeped in violence, and I don’t just mean the fight scene.

The most striking thing about this page is the colour scheme. The panels consisting of the interview where all of the dialogue originates are situated on the left, and consists of subdued colours: Dr Manhattan’s blue skin, the black backgrounds and the greens of the audience. On the right, the fight scene plays out over a red background with vivid oranges and yellows to create a sense of anger, urgency and action.

But what is so immensely clever about the use of colour on this page is how Moore picks three objects from the panels representing the interview scene to share the colours of the fight scene: the red pocket square, the yellow press badge, the orange TV camera. Moore singles these out as objects that pertain to violence in a personal attack against the media (but that is a whole different can of worms).

But as you read it, Moore’s genius use of dialogue draws you into the interview while it enhances the action. In doing so he doesn’t allow the action to overshadow the interview. On the second panel, the host tells a reporter to “keep it snappy” in relation to his question. However, by layering this particular piece of dialogue over the sudden movement of the two superheroes springing into action, the word “snappy” (also portrayed in bold letters) becomes an aid to the visuals.

The same can be said again of the fourth panel when the effect is used once more where the questioner remarks that he believed “it was quite sudden and painful” over the image of a man’s nose getting broken. The dialogue from one scene is actually enhancing its counterpart.

The words lend themselves to the physical attacks being portrayed by the superheroes on one side of the page but simultaneously highlight the verbal attack of the human. So we are seeing a sort of dichotomy of violence as we witness superheroes attack humans physically on one side, but on the other side we observe a human attack a superhero verbally.

As the scenes are not connected, Moore is showing verbal and physical violence to be two sides of the same coin and that they can have equally devastating effects on the victim. Consider the very shapes of the patterns of the panels that represent each scene. They are exact opposites and so fit together like two Tetris pieces to form the whole.

This technique is difficult and Moore makes it look effortless. But if you get it right then it pays dividends.

Let’s move on to another famous comic in 100 bullets. The example below is a bit easier to go through because it takes place over a great deal more pages.

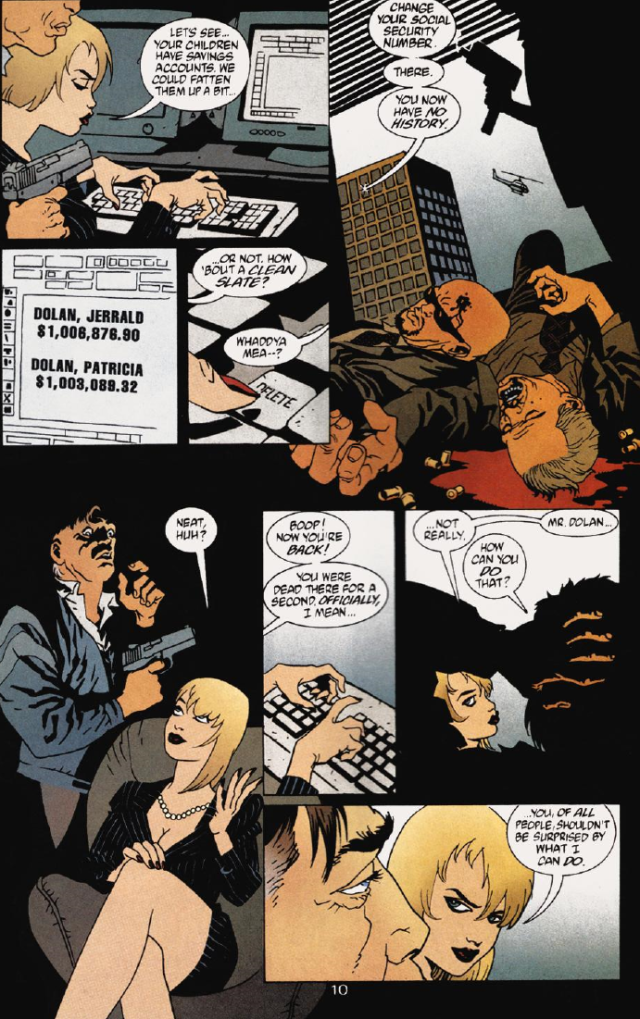

Once again the violence is prevalent, but I’m not going to dwell on it as much. Brian Azzarello has two characters conduct a lengthy conversation in a dark office across several pages. Because of this, the number of angles is already limited and although the conversation is an darkly intense one, boredom would eventually set in due to the repetitive visuals. How does Azzarello solve this problem? He intersperses this scene with a completely unrelated conflict that escalates across the street.

On the above example there is only one panel which shows the aftermath of said conflict, a double murder. But it doesn’t end there. As the two main characters continue to talk, this incident which has no bearing on the story and involves characters we have never seen before plays out regardless and before we know it we have hails of bullets and a helicopter being blown out of the sky. Unlike the Watchman example, the people in this extra scene are not part of the main story. This random act of violence flits by us innocuously and gives us an insight to the world in which Azzarello bases his story, much like Moore, he is giving his world depth by showing that the scene involving the main characters is not the centre of the universe.

The final example I will try and refrain from gushing about too much. The following page is from Will Eisner’s “A life Force” which is collected in the must read “A Contract with God” Trilogy.

Set in 1940’s New York and a reflection of the world Eisner grew up in. What is instantly so wonderful about this is the authenticity of the dialogue. You can’t help but hear the accent that would have been so prevalent in the Bronx at that time.

But it is the body language and the facial expressions that Eisner captures that really draw you in. In his book Comics and Sequential Art, Eisner advocates exaggerating the body language of the character akin to that of a pantomime to maximise the emotion in each panel. He is right of course, comics is a silent medium, we have no soundtrack to cue the emotive state of any given moment, nor do we have the luxury of space to show or describe a characters emotion. But although Eisner’s characters are exaggerated in their movement and facial expression, Eisner is able to rein it in just enough that it never crosses the line from believable into pantomime. So the scene plays out more like a play.

Take panel 5 for example, since there was no dialogue it was likely you gave it more of a glance as you moved from panel 4 to 6. But therein lies Eisner’s genius. Take a moment to really look at them. You’ll see a range of emotions portrayed in the faces so complex that dialogue is of no use. That is the mark of a great artist. And because these are the type of people Eisner would have encountered so frequently in downtown tenement buildings, this absence of dialogue creates something incredible and even after a mere glance while reading the page, Eisner has subtly drawn us in with their facial expressions.

Let’s look at Panel 4 again; there is mildly exaggerated body language (the man with his hands over his face and the woman’s outstretched hand. Both instances work with the dialogue. On panel 6, there is hardly any physical exaggeration of body language, but also less dialogue. So when we once again focus on the panel between them, we see there is no exaggeration of body language as well as no dialogue. Because of that, panel 5 does not look like a pantomime like panel 4, or a more serious play like panel 6. No. Panel 5 is a glimpse of the real world. And although the role of comics is usually to take the reader away from the world for a while, Eisner reminds us that at the centre of everything are these moments. That is why the panel is right in the middle of the page, because it holds everything around it together. It is the axis of the page upon which everything turns. The mark of Eisner’s unparalleled talent and insight to the world.

I used to be terrified of writing “silent” panels. To me it was like having a blank scene during a film or a pause during a song. And it wasn’t until I read Eisner that I realised it was in fact a manifestation of my own insecurity as a writer.

Our viewpoint hardly changes (7 out of the 9 panels are roughly similar) but that is also the case in the theatre. We sit at a stationary point and view everything from the same perspective. Yet we don’t readily complain about the lack of alternating angles.

Now the panels aren’t particularly exciting in comparison to the previous two examples but the combination of Eisner’s skill as an artist with the authenticity and emotion of the dialogue means that we don’t need anything to break up the scene. Instead we witness something genuine and intimate, and to take that away would only be to the detriment of the connection we have to it.

This, ladies and gentlemen is why Eisner is regarded as the greatest comic creator of all time.

So there are three ways to portray conversations while keeping your reader hooked. I hope you learned something from these examples like I did and use it to improve your own creations. If you want to explore visual depictions of dialogue in comics, please check out my long overdue follow-up here!

Thanks for reading this. If you liked this, consider saying hello! If you REALLY liked it and want to see more of me, you can follow me at any of the following links.

Or, if you want to dive more into topics like this, please consider buying my eBook of which this article is a part of. Fifteen articles covering numerous aspects of writing and fundraising comics. (Full contents below)

You can purchase it here:

Here is a peek at the contents

1.The Art of Conversation, Depicting dialogue in comics (You can read this for free on my blog)

2.The Art of Conversation Part 2, representing dialogue in comics

3.Black holes disguised as white lines; the power of the comic gutter

4.A Picture is Worth 1000 words – how to write a comic script that your artist can use Part 1

5.A Picture is Worth 1000 words – how to write a comic script that your artist can use Part 2

6.Write to the beat of your own drum – How to pace scenes in a comic

8.The Internal and External Drives of a Narrative.

9.The terrifying REAL cost of creating a comic issue

10.Lessons that turned a failed comic Kickstarter into a successful one.

11.No Snakes, Only Ladders: Kickstarter Reward structuring

12.Kickstarter Capitalism: the worth of debut and returning creators

13.Surviving your maiden Kickstarter Part 1 – Failure to prepare is preparing to fail

14.Surviving your maiden Kickstarter Part 2 – The Campaign Trail

15.Surviving your maiden Kickstarter Part 3 – Crossing that finishing line

Pingback: A Picture is Worth 1000 words – how to write a comic script that your artist can use Part 2 – Richard Mooney

This was very helpful, thank you! I’ve been a bit concerned about depicting long conversations in my upcoming comics projects in a way that is interesting (they are romance-focused, and conversation is a major part of the genre), and this has assuaged some of that concern :).

LikeLike

Thank you Ashley, in romance, long conversations are necessary so readers will expect them at some point. But there are always other things you can do to ensure that new fans to the genre are still engaged during these long conversations.

LikeLike

Pingback: Write to the beat of your own drum – How to pace scenes in a comic – Richard Mooney

What a timely piece today! Thank you so much for such a good post.

I saw your books earlier, but this one I believe on of the

the best, same as this one https://shadbushcollective.org/managing-your-finances-as-an-apprentice/. How can you find so many

details? I like how you organize everything, since it’s really easy to read.

All in all, I can recommend this article to everyone who’s interested in that topic.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Art of Conversation Part 2, representing dialogue in comics. – Richard Mooney

Thank you so much for putting this together. I really appreciate this resource. I am writing a grounded fantasy graphic novel and I am currently story boarding a long conversation between two of my main characters. I have been having trouble keeping the flow of the conversation while still making it interesting to read. I am going to try some of the things mentioned here and see if I can’t rework it a bit.

LikeLike

That is always the most difficult point to keep readers engaged. Despite long conversations happening in our daily lives, when we are not actively participating it is harder to stay interested! Good luck and I hope this article helped!

LikeLike

Pingback: Vault Comics FREE FIRSTS – Top 10 – Richard Mooney